Godot

Active Member

- Joined

- May 9, 2007

- Messages

- 186

- Car

- A180 CDI Elegance Auto 3 Door Panoramic Sun Roof, Bi Xenons

A 1940s Rolex chronograph that belonged to a British prisoner of war at Luft Stalag III camp in Nazi Germany came up for auction sale in Geneva in May, 2007. With it is the logbook Corporal Clive Nutting of the Royal Corps of Signals kept during his wartime captivity. It’s a collection of unpublished cartoons, illustrations and photographs revealing a new insight into camp life and the mass breakout of 76 POWs made famous in the movie, The Great Escape.

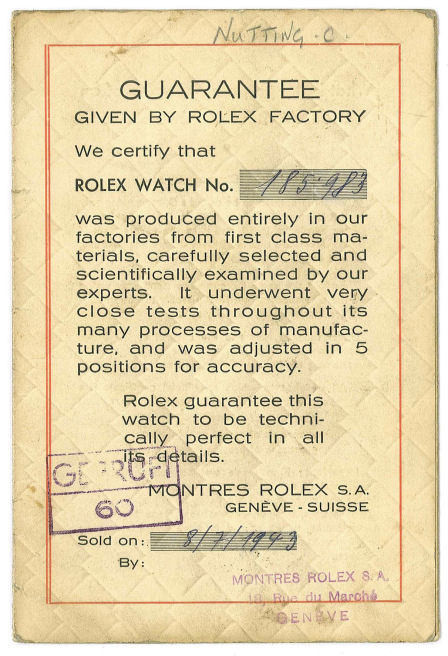

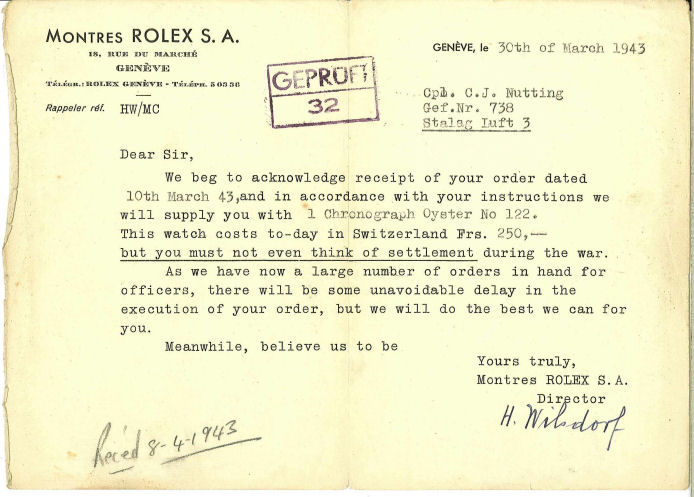

Included in the papers is Nutting’s correspondence with Rolex, confirming the remarkable marketing campaign the Geneva brand launched during World War II.

A Captive Market

Swiss watch sales were badly hit by the war, especially after Germany invaded unoccupied Vichy France in November 1942, and neutral Switzerland found itself completely encircled by Axis powers. Watch companies were cut off from their best customers, the British and Americans.

Rolex, however, discovered that there were plenty of British and Americans right on Switzerland’s doorstep — literally a captive market — in German prisoner-of-war camps. Stalag Luft III, for example, housed up to 10,000 Allied airmen, shot down in operations over occupied Europe. Thousands more Allied officers were interned in the various Oflag (officer’s POW camps) scattered throughout the German Reich.

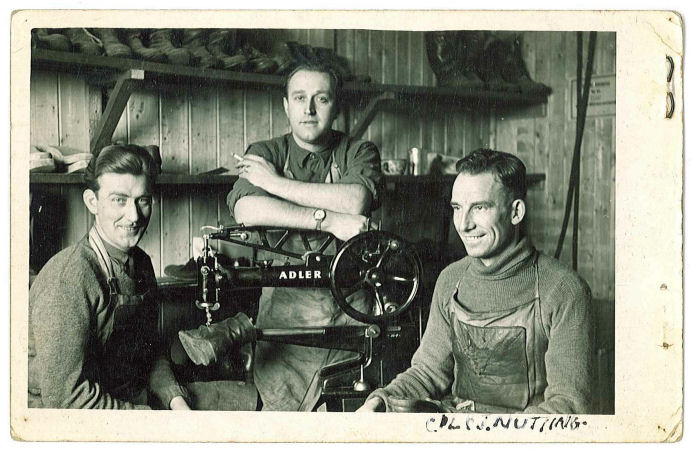

Clive Nutting (at right) with his “Brothers in Arm” in Stalag Luft III

This was evidently a booming market, judging from Rolex’s confirmation of an order for one of its more expensive watches received from prisoner No. 738 in Stalag Luft III. Hans Wilsdorf, founding director of Rolex who took personal charge of sales to POWs, warned Clive Nutting of “an unavoidable delay in the execution of your order.” The delay was due, not to wartime restrictions, “but to a large number of orders in hand for officers.”

Rolex’s Incredible Offer

The large number of orders is explained by the incredible offer Rolex was making to POWs. Underlined in Wilsdorf’s letter to Nutting are the words, “…but you must not even think of settlement during the war.” The news that Rolex was offering watches on the “pay-on-the-never-never” plan spread through the camps like wildfire. More than 3,000 Rolex watches were reportedly ordered by British officers in the Oflag VII B POW camp in Bavaria alone.

Wilsdorf, himself a German, was betting on an Allied victory. By early 1943 this was a risk worth taking; the tide of war had turned. The Russians were on the offensive after routing the Germans at Stalingrad; German and Italian armies were being driven out of North Africa. This expression of trust must have been a wonderful morale-booster for the POWs. Besides being a comfort in a POW camp, watches were part of an airman’s kit, and many had lost theirs on capture or in trying to avoid it. As a signaller, Clive Nutting would also have been issued a watch as part of his equipment. For escape-minded prisoners who could only get to the borders by public transport, a watch was as essential as a train timetable.

Wilsdorf further hedged his bet by making this offer available to British officers only, in the belief that their word was their bond. He had started his watch business in England, but moved to Switzerland after World War I for tax reasons. He was also impressed by the fact that Rolex watches were popular among British Royal Air Force pilots. He also extended the offer to NCOs like Clive Nutting, who though not an officer nor even in the air force, was gentleman enough to order a 250-franc Rolex 3525 Oyster chronograph. Most other POWs ordered the much cheaper Speed King model, popular for its small size.

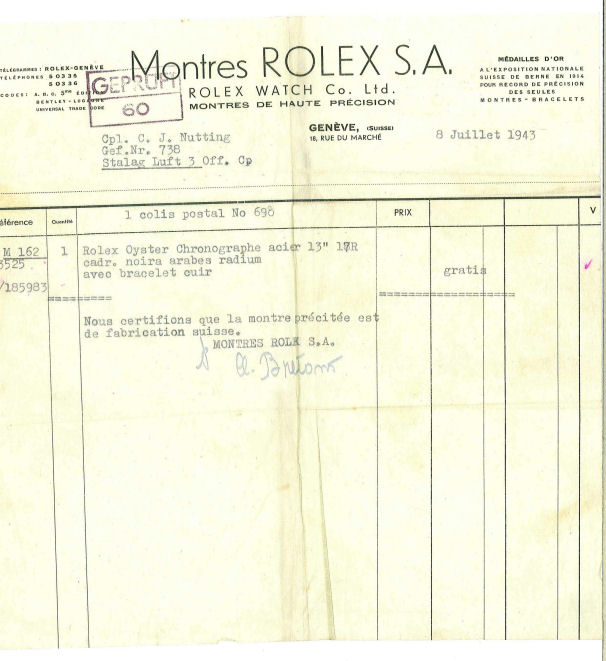

Nutting’s Oyster chronograph No. 122, ordered on March 10, 1943, was eventually sent on July 10 with a gratis invoice, certificate and instructions, and it was on Nutting’s wrist by August 4. As a chronograph, it could well have been used in timing the patrols of the goons (prison guards) or the despatch of 76 escapees though tunnel “Harry” in the mass breakout of March 24-25, 1944.

A Valuable Craftsman

Nutting was among a few army personnel quartered in the North camp of Stalag Luft III. A shoemaker by trade, he was valuable both to the Germans and to the POWs. He had a privileged position in charge of the camp’s shoemaking workshop, received a wage from the Germans, sent remittances to his family in England, and as an officer’s promissory note testifies, had money to lend. He could evidently afford a special watch.

Clive Nutting (at right) with his friends in the workshop

The next we hear of the watch is on Nutting’s return to his home in Acton, London, in August 1945 when he writes to Wilsdorf that although his watch served well in the cold weather during the evacuation of the camps, it was now gaining an hour a day. Where can he have it fixed? And can he have the final invoice?

Due to British currency restrictions, Rolex could only send Nutting the invoice of £15 12s 6d for his watch in 1948. The chronograph stayed with him until his death in Australia in 2001 at the age of 90.

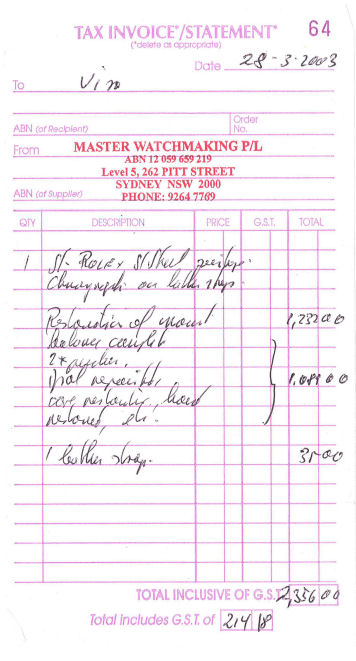

The last record of Nutting’s POW watch is a restorer’s bill for $2,356 (Australian dollars), dated March 28, 2003 — exactly 63 years after its original owner became a prisoner of war.

The restorer’s bill dated March 28, 2003

To Be Continued . . .

Last edited: