Le Mans 1990. Chicanes and redemption

I must confess at this point that I have never actually worked in F1, in fact I’ve managed to stealthily avoid it all my life!

I was asked at the end of ’87 by Ross Brawn to race engineer for Arrows, but had to I say that I still had unfinished business at Jaguar at that time, as we were yet to win at Le Mans.

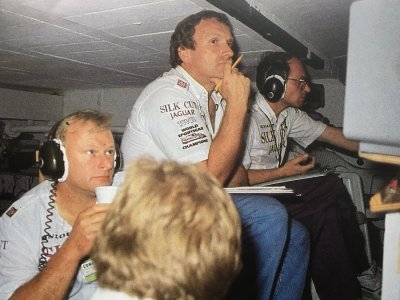

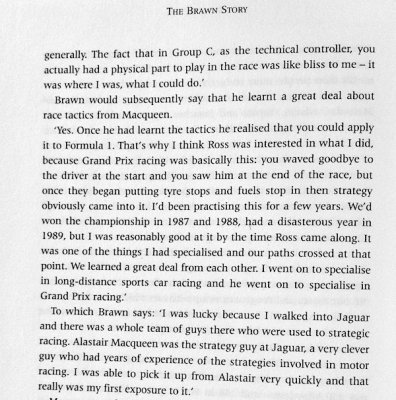

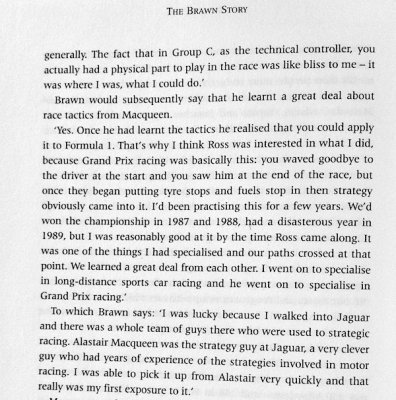

In a quirk of fate, it was Ross who came to join me at TWR Jaguar at the start of 1990 as Technical Director and design a new 3.5L atmo car for new Gp C regulations of 1991.We quite literally shared a desk for the first couple of months whilst his new design office was built. We shared a great deal of information and Ross was generous enough to credit me in his book with his introduction to race strategy.

Ross came to first couple of races in 1990 but then devoted the majority of his time to the design his iconic XJR-14.

With Tony Southgate now gone from the team and Ross busy, it was down to me to develop a car to suit the ‘new’ circuit at Le Mans with importantly, the Mulsanne straight now broken in to three sections with two new chicanes. I’d spent a couple of weeks in the Imperial Collage wind tunnel at the end of 1989 concentrating on the most efficient aero possible from this series of Jaguars with a ‘medium’ level of downforce. With none of the circuit and driver simulators we take for granted these days, it was very much a case of careful calculation and big dose of experience.

Without the need for the a massive top speed as in previous years, we would be running more downforce, going quicker in all the corners and inevitably running more drag….but we didn’t get an increase in the 2500L fuel allowance for the 24 hours.

I had the benefit of 4 years of running the cars at Le Mans by that stage and importantly, the performance details of having run 3 very different downforce levels on my first visit to the circuit for the test day in 86.

I knew the car had to give the best aero efficiency ever, and that we would probably want a drag level similar to that run at Monza, but the big puzzle was where the aero balance would have to be. Most racing cars typically run the aero ‘split’ at the same point as the c of g of the car. So, if you have a 40:60 weight distribution, you want the downforce to act in the same place to maintain the balance throughout the speed range. The old Mulsanne straight with it’s constant high speed on a truck rutted real road would not tolerate this. Drivers said they felt the car would spin as soon as the thought about steering at over 200mph, which at night, in traffic, in the dark is… errr…uncomfortable!

Having the centre of pressure on or ahead of the centre of gravity is unpleasant, ever driven an old VW kombi van in a high cross wind?

A typical aero split on the old circuit was about 28 to 30%.

After much debate, mostly with myself, I decided to centre the maximum efficiency around a 38%, about 3% back from our sprint car setting reasoning that it is much better to deal with a slight understeer at high speed than having the car trying to swap ends. On-circuit tuning aids would allow me to alter that by about +/- 3%, but with some loss of efficiency.

Adding NACA ducts in place of active scoop inlets was aiding the efficiency, but it was the position of the rear wing to get the airflow from both the underside and topside of the car to combine effectively which was the biggest step forward. I ended up using a 2 piece wing with the main plane in a 5 deg. nose up attitude to match the flow regime off the tail, set at the optimum height and distance back.

The lift to drag ratio on the low drag 88/89 car was around 2.8. On the 90LM car it was 4.0. Better even that on our high downforce ‘sprint’ cars.

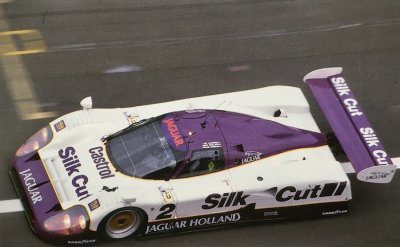

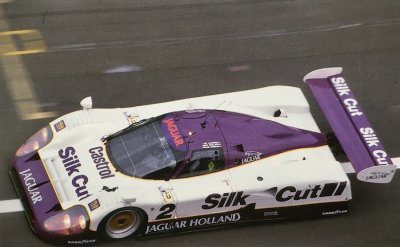

This is the 1990 spec LM car. Note the low drag NACA intakes, the nose up rear wing main plane, BBS wheels and Goodyear tyres.

Just to add to the gamble was the fact there would be no traditional test day in May, so when you pitched up for the race, it was going to be very much ‘run what you brung’

One real positive was that Martin Brundle was back in the driver squad after playing with F1 cars in ’89 and we had already won the Silverstone 1000kms together in the turbo car just prior to Le Mans. It was his 2nd and my 4th win at that race.

Having worked with each other for many years we had developed an almost telepathic understanding of what was required to get the best out of the car.

When the first red flag came out during the first test session (to remove Johnathan Palmer’s wrecked Porsche from the straight between the new chicanes!) Martin comfortably topped the time sheets with the very minimum of adjustment. He was happy that the car felt just right, and while we knew we would not stay quickest as the turbo’s were turned up, we could get on with race running whilst the Porsche’s faffed about with short and long tailed versions of their cars.

Jaguar went on the to finish the first ‘chicane’ race in first and second positions, but it was far from a flag to flag victory, battling throughout the race with our old adversary Porches, and seven(!) Nissans. Two of the four Jaguars which started were sacrificed to the perils of the race, and only in the final half hour was second place secured as one of the Porches expired.

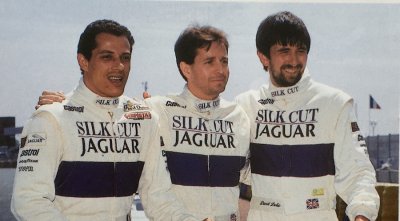

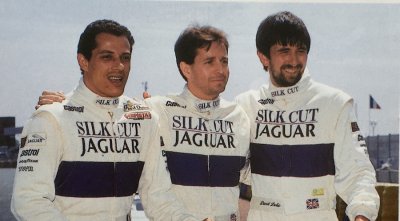

Drivers of car 1. Fast Frog Ferte, Martin and the late David Leslie who had been my first F3 driver back in 1981.

My no.1 car was one of the Jaguars to retire with overheating and eventual water pump failure, but Martin still got to win the race in the no.3 car.

The rules of the time said that a driver could swap cars within the team provided no more than 3 drivers actually drove the car in the race.

After my car pitted from the lead and lost 4 laps at about 8pm, Martin was rested after midnight and was going to be put back in the either car 3 (which was using just 2 drivers up to that point) or car 1 depending on the position and state of the cars early in the morning.

The overheating didn’t go away on my car and it retired at 6am. By that time car 3 was still going well but Price Cobb was completely wasted, so Martin joined ‘big’ John Nielsen in car 3.

Together they drove the car to the finish. John was just unstoppable. He was the sort of guy that if the car had a problem out on the circuit, you expected him to return to the pits on foot with the car tucked under his arm! He drove 17 stints in that car and Martin a total of 10 in the two cars.

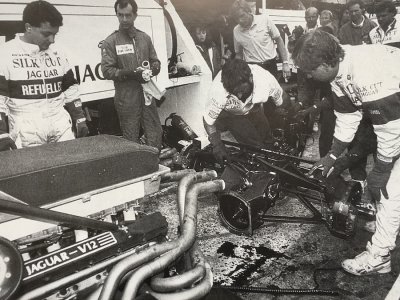

This car was being run by our American IMSA squad, and they had fitted some very smart American made, billet, ‘Fat Pad’ calipers which were claimed and tested by them to reduce the number of pad stops required during the race from 3 to 2.

They worked really well and by lunchtime on Sunday, the car was leading and enjoying a 2 lap cushion over its pursuers after just one pad change.

On the second change, one of the extra long caliper pistons decided to seize in the bore and a new caliper had to be fitted. Fortunately these were fitted with dry break connectors so only 1.5 laps were lost.

Now what was my Le Mans mantra? ‘If it’s new it will give a problem’

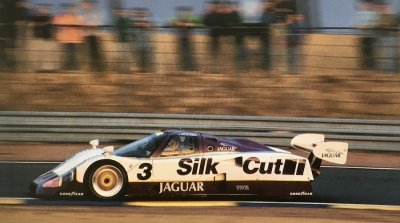

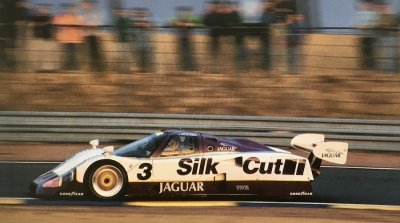

The winning car 3 with ‘big’ John Nielsen at the wheel. If you can spot the vertical line half way along the big side NACA duct, (below the ‘K’) it was one of several sizes of angle we could clip on to the car to trip the flow into the oil coolers and so regulate the oil temperature. An idea a borrowed from the cabin air intake duct on a 737. I must have spent too much time queuing to get on aircraft!

This was the Le Mans win I am most proud of and the one I contributed most to. We fought hard all the way for victory, even if I wasn’t race engineering the winning car. Tired and happy, I fell to sleep face down in my dessert on Sunday evening having been awake for over 40 hours.

Such a glamorous, carefree and relaxing world is motorsport!

Our wheel and tyre suppliers recognised my contribution by donating me a new set of BBS forged wheels and a set of Goodyear’s finest tyres to go on my 124 Mercedes estate road car. These were duly fitted with a new set of Mercedes Sportline suspension by the dealers in Oxford. It was the sort of car that ‘big’ John might have driven, but was actually used mostly by my wife. A few years later, its replacement was sold to me by Brundle Lexus….

Tom was well pleased and 'rewarded' me with new position heading up the development of the world's fastest road car, the XJ220, at the end of the season. You learn not to say no to Tom’s requests.

So my last task that year in TWR racing after completing the Gp C season was to do the c of g calcs. for Ross’s XJR-14. He had never done an ‘asymmetric’ car before and was very concerned about the driver not sitting on the car centre line!

Then into the alien world of road cars….oh! except I had to go to every F1 race that hosted a round of the Jaguar XJR-15 challenge to race engineer and, of course, back to Le Mans to advise and race engineer one of the cars….and get paid for enjoying my hobby.