When nobody waves the chequered flag.

At its heart, motorsport is a fairly simple sport. Go fast, don’t crash until you see the chequered flag. Whether that’s at the end of a prescribed distance or time, if you reach it first or in the quickest time, then its job done.

With the exception of one year of my motorsport life, these rules applied. That year was spent setting a diesel landspeed record. The thought of the chequered flag never entered my head until the final day we set our target record, but then nobody was there to say the job was officially over, nobody to wave that flag. We could potentially go out the following day and go quicker. That was to become, probably, the hardest decision to make.

I was working in the paddock at Oulton Park in March 2006 when I had a phone call.

I’ve had quite a few memorable moments there. As a school kid in the early 60’s I’d got to meet and talk to my hero Jim Clark. My father was at school in Duns, Jim’s hometown, so there was a connection and we all chatted happily as he prepared to drive his Lotus 23.

In 1998 I stood half asleep and soaked in Champagne after a McLaren GT race win following an all-night drive back from running the same car at a Le Mans test day the previous day.

In 1999 I watched my son celebrate his first ever motorcycle race win there, then went on to have dinner that same evening with acting legend Sir Tom Courtney.

In 2000 I’d spend a full afternoon in a paddock full of carnage when running a whole race full of Palmer Audi cars. We had made 2 earlier attempts to run the race, each one ending in a huge pile of cars at the first turn. The drivers were all young hot-shoes and accidents were certainly the norm, but that afternoon would become known as ‘Palmergeddon’

This time it was design engineer John Piper on the phone who was one of the guys Ross Brawn had brought to TWR Jaguar and he had designed the gearbox/transaxle for the XJR-14. He had also race engineered a car at Le Mans for me in 1991.

He said he’d almost completed the design of a very special car and was looking for somebody to run it.

It turned out to be the JCB Dieselmax landspeed record car. My job would be to oversee the build, plan and implement the test plan, the verification and run the car out at Bonneville salt flats. Almost exactly what a race engineer does in motorsport.

John’s premise was wonderfully simple, when the car is on stands then I’m in charge. When it’s on its wheels then you’re in charge. Suddenly, all other work became less important and I switched focus to August in Utah.

Of course, the main job of the race (or in this case ‘run’ engineer) is to be the link between the driver and the team and optimise the speed of the car. This time my driver was the fastest man on earth and the only one to have exceeded the speed of sound on the ground, Andy Green. He was also a highly qualified fighter pilot, a great mathematician, leader of the RAF Bobsleigh Cresta run team, keen freefall parachutist and the Base Commander of a RAF Wittering near Peterborough.

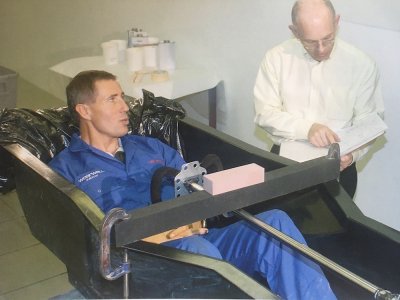

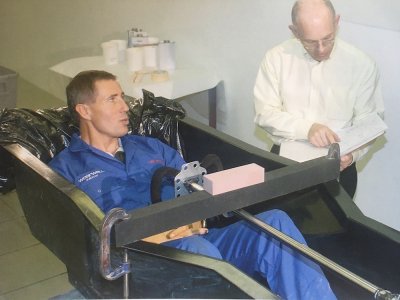

Here I'm starting to find out exactly what Andy wants in the cockpit and where.

Turned out like this:

Andy had already cleared with the RAF that we could use the runway there to test the car at up to 200mph prior to leaving for the States, if we avoided the Harriers….

Andy had also put some of his old ‘Thrust’ landspeed team back together including Richard Noble (former record holder) and astonishing aerodynamicist Ron Ayres. He was the father of the bloodhound missiles from the cold war era and the only man who could keep a ‘projectile’ on the ground as it went supersonic. It was a whole new experience to work with such acclaimed people from outside the world of motorsport.

Ron Ayres is real legend. He had studied landspeed record attempts for many years and been struck by the fact most had come up short of their theoretical speeds when run on the salt. He had established a theory of ‘Spray drag’. In short, it says that when you run on a loose surface such as the desert or salt, that because of plumes of dust behind the vehicle, it is actually passing through a more dense fluid than air, and had formulated an equation to establish its value. Dieselmax was designed with underbody aerodynamics specifically to reduce the spray thrown up by the wheels. There was never a plume or rooster tail following this car on the salt. As the speed of the car increased, I was able to verify every one of his predicted aero figures to a number of decimal places. Really low drag, lift neutral and great stability.

No salt spray from this car!

JCB were keen to promote their new 444 diesel engine now being used in a variety of their products.

Being asked to set a landspeed record with a couple of ‘digger’ engines still ranks as one of the stranger requests I’ve had. But if I can get two Le Mans wins with a V12 ‘aeroplane’ engine, then anything seems possible if you have the resource, technology and time.

Riccardo had the job of developing the JCB 444 diesel engines, normally happy to pump out less than 100bhp, into units producing almost 800bhp….each! That required a little work(!) and whilst still being true to the base engine, they increased in size from 4 to 5 litres, got steel pistons, injectors the size of bath taps and sequential turbo charging with the final turbo much the same size as a dustbin lid. The two engines were completely independent of each other apart from a feed from the throttle pot and gear position signal.

To give the lowest possible frontal area the engines would sit in front and behind the driver, with the rear engine in a conventional ‘race car’ position ahead of the rear wheels and the front engine just behind the front wheels driving the front wheels.

Calculations indicated that the car would be more efficient with no conventional radiators but a heat exchanger set-up through an ice tank housed in the carbon nosebox of the vehicle. Every run with this system was a prototype. Adjustments were being constantly made to allow us to use the full thermal capacity available whilst holding the engine temperature to allow maximum power through each 11-mile pass.

The schedule to get the car designed, built, tested and flown to the States was optimistic to say the least. Inevitably, a six week build period spread to 6.5 weeks at which point we decided to move the almost complete car to RAF Wittering whilst we waited for the completion of the final few components. The car was put together at Visioneering in Coventry, a specialist engineering firm run by Brian Horner. F1 fans may well recognise that surname.

I’d put together a run plan for the car together with a sign off document which ran to some 140 separate systems and parts. It would work on a traffic light principle, and if there we no red lights after the Wittering trials, then we would pack the car off to Bonneville.

Working together almost around the clock for ten days allowed the all new team to gel and after over 20 runs we had that had achieved over 200mph in the space available on the runway and had only a couple of ‘amber’ warnings on the sign off document.

We had the green light for an assault on the salt!

Bonneville is like nowhere else on earth. In the winter it is a shallow salt lake which dries out in summer to form a dry lake bed with a flat and smooth (ish! depending on the weather) of some 46 square miles. Conditions vary from year to year and it sits at about 4200’ altitude, much the same as the top of Ben Nevis. The grip level on normal tyres is equivalent to wet tarmac and it took me quite some time to get used to a bright white surface which wasn’t as slippery as ice or snow. The light levels are something else, think sunshine on Alpine snow then double it. It’s somewhere you can suffer sunburn on the underside of your nose from the reflection. Ambient pressure is around 860 mb.

I was also in charge of the 'chutes. Developed by Andy and I as the testing progressed.

One of the biggest issues we faced prior to getting to Bonneville was finding tyres which would support our 2.7 tonne car at 350mph. We had settled on some 23” Goodyear drag race tyres which were validated to 300mph, then done our own tests to validate them to 350mph in very specific conditions on a rig at a USAF base used to develop the space shuttle tyres. With the correct run profile and pressures, they were capable of two 11 mile runs at that speed and load simulated on the steel roller rig.

The Bonneville program started at the annual ‘run what you brung’ Speed Week as practice, then a week of preparation including changing both engines to ‘record spec’ prior to an exclusive record week with the FIA in attendance. We were based a few miles from the salt flats at Wendover airport in a WW2 wooden framed hanger famous for housing the ‘Enola Gay’ aircraft the night prior to her little trip to Hiroshima in 1945…

In ‘that’ hanger

Speed week was a big learning experience and despite all that space, it wasn’t until the final day that the car ran over 300mph. There were, of course, all the normal little glitches of running a prototype, but the one that had us most perplexed was to become known as ‘lazy man on a tandem’ syndrome.

We were having trouble get one or other of the engines to spool up its turbos on the salt.

This had not been an issue on the dyno as the engine was always run against the resistance of the dyno brake to gain exhaust temperature, then the thermal inertia would spool up the turbos on request. It was never a problem at Wittering as the ambient pressure had been about 1000mb. But now with only 860mb pressure, one engine would start to spool up, take the load off the other and without load it would just give up and go along for the ride!

Just like the lazy tandem rider.

We tried pre-heating the engines to different levels, but as soon as one took off, the other would just become plain lazy! That slight ambient pressure drop had tipped our whole system over the edge.

There are very few people who have ever faced that problem (!) so we were really were pioneering.

Then it dawned on us......Andy and I confirm a few final details as the sun comes up over the salt

We plotted to attack the issue on two fronts. Firstly we would fit a 1” dia boost share line between the two engine plenums so that the engine that boosted first would share it around a bit.

We would also get Andy to load the engines against the brakes and have the exhaust gas temps displayed on the dash so he could see over 600 deg on each engine before allowing them to rev. So on the final day of speed week we set a record 317mph.

During our week of downtime we needed not only to rebuild to car but also to perfect our engine heating strategy by doing some low speed testing at Wendover airport.

The first run. with the new engines was halted when the rear engine refused to come on boost. After a few hours of digging into the data, it was spotted that the rear engine was seeing a false neutral signal from the gear box and was doing exactly what it was told and limiting its revs to 2800.

The following day, an electrical issue in the front loom meant we aborted the first run of the day, but by 10:30 that morning we had a new record of 328mph, with the return run at 342.

At the crack of dawn on 23 August our outbound run was 365mph. The tyres looked brand new, the cooling was almost perfect and Andy had not yet got into 6th gear.

The turnaround was completed in under 40 minutes and the car set off on its return run.

As we chased in our road cars it became clear that the big yellow car was not streaking away from us. Andy was on the radio saying the front engine was not boosting, but would give the brake loading one more shot. I thought that we had just wasted a good outbound run and my mind shifted to the plan for the following day.

But then, about a mile later into the run than it should have, the car came on to boost.

Talk about turbo lag! Andy then gave it the full beans and passed through the measured mile at 335mph, that’s what a mile less run up does.

The FIA announced the average as Andy came to rest at the end of the run 350.092mph.

It was very clear the car could go quicker. The tyres looked in fine shape and we had seen them to 400mph on a ‘free spin’ rig.

We had the team in place. If we hadn’t got ‘greedy’ with front engine start temperature we could do 2 x perfect runs. We still hadn’t turned the engines up to ‘11’. We hadn’t even run 6th gear yet! The salt was in the best condition for years and we had the place booked for another three days.

375mph looked entirely possible.

As the management team sat and discussed the possibilities we had all been infected by a very strong virus the locals call salt fever. Even Andy, normally the most controlled and rational person, was infected.

As our adrenaline levels subsided, so the prospect of running again looked more unlikely.

In the end we all agreed that to risk that we could come back with a better car and certified tyres another year, was much better idea than risking Andy the following day.

But it took us some hours to make that decision. But where was the man with the chequered flag?

The record has never been approached in the last 14 years.

At its heart, motorsport is a fairly simple sport. Go fast, don’t crash until you see the chequered flag. Whether that’s at the end of a prescribed distance or time, if you reach it first or in the quickest time, then its job done.

With the exception of one year of my motorsport life, these rules applied. That year was spent setting a diesel landspeed record. The thought of the chequered flag never entered my head until the final day we set our target record, but then nobody was there to say the job was officially over, nobody to wave that flag. We could potentially go out the following day and go quicker. That was to become, probably, the hardest decision to make.

I was working in the paddock at Oulton Park in March 2006 when I had a phone call.

I’ve had quite a few memorable moments there. As a school kid in the early 60’s I’d got to meet and talk to my hero Jim Clark. My father was at school in Duns, Jim’s hometown, so there was a connection and we all chatted happily as he prepared to drive his Lotus 23.

In 1998 I stood half asleep and soaked in Champagne after a McLaren GT race win following an all-night drive back from running the same car at a Le Mans test day the previous day.

In 1999 I watched my son celebrate his first ever motorcycle race win there, then went on to have dinner that same evening with acting legend Sir Tom Courtney.

In 2000 I’d spend a full afternoon in a paddock full of carnage when running a whole race full of Palmer Audi cars. We had made 2 earlier attempts to run the race, each one ending in a huge pile of cars at the first turn. The drivers were all young hot-shoes and accidents were certainly the norm, but that afternoon would become known as ‘Palmergeddon’

This time it was design engineer John Piper on the phone who was one of the guys Ross Brawn had brought to TWR Jaguar and he had designed the gearbox/transaxle for the XJR-14. He had also race engineered a car at Le Mans for me in 1991.

He said he’d almost completed the design of a very special car and was looking for somebody to run it.

It turned out to be the JCB Dieselmax landspeed record car. My job would be to oversee the build, plan and implement the test plan, the verification and run the car out at Bonneville salt flats. Almost exactly what a race engineer does in motorsport.

John’s premise was wonderfully simple, when the car is on stands then I’m in charge. When it’s on its wheels then you’re in charge. Suddenly, all other work became less important and I switched focus to August in Utah.

Of course, the main job of the race (or in this case ‘run’ engineer) is to be the link between the driver and the team and optimise the speed of the car. This time my driver was the fastest man on earth and the only one to have exceeded the speed of sound on the ground, Andy Green. He was also a highly qualified fighter pilot, a great mathematician, leader of the RAF Bobsleigh Cresta run team, keen freefall parachutist and the Base Commander of a RAF Wittering near Peterborough.

Here I'm starting to find out exactly what Andy wants in the cockpit and where.

Turned out like this:

Andy had already cleared with the RAF that we could use the runway there to test the car at up to 200mph prior to leaving for the States, if we avoided the Harriers….

Andy had also put some of his old ‘Thrust’ landspeed team back together including Richard Noble (former record holder) and astonishing aerodynamicist Ron Ayres. He was the father of the bloodhound missiles from the cold war era and the only man who could keep a ‘projectile’ on the ground as it went supersonic. It was a whole new experience to work with such acclaimed people from outside the world of motorsport.

Ron Ayres is real legend. He had studied landspeed record attempts for many years and been struck by the fact most had come up short of their theoretical speeds when run on the salt. He had established a theory of ‘Spray drag’. In short, it says that when you run on a loose surface such as the desert or salt, that because of plumes of dust behind the vehicle, it is actually passing through a more dense fluid than air, and had formulated an equation to establish its value. Dieselmax was designed with underbody aerodynamics specifically to reduce the spray thrown up by the wheels. There was never a plume or rooster tail following this car on the salt. As the speed of the car increased, I was able to verify every one of his predicted aero figures to a number of decimal places. Really low drag, lift neutral and great stability.

No salt spray from this car!

JCB were keen to promote their new 444 diesel engine now being used in a variety of their products.

Being asked to set a landspeed record with a couple of ‘digger’ engines still ranks as one of the stranger requests I’ve had. But if I can get two Le Mans wins with a V12 ‘aeroplane’ engine, then anything seems possible if you have the resource, technology and time.

Riccardo had the job of developing the JCB 444 diesel engines, normally happy to pump out less than 100bhp, into units producing almost 800bhp….each! That required a little work(!) and whilst still being true to the base engine, they increased in size from 4 to 5 litres, got steel pistons, injectors the size of bath taps and sequential turbo charging with the final turbo much the same size as a dustbin lid. The two engines were completely independent of each other apart from a feed from the throttle pot and gear position signal.

To give the lowest possible frontal area the engines would sit in front and behind the driver, with the rear engine in a conventional ‘race car’ position ahead of the rear wheels and the front engine just behind the front wheels driving the front wheels.

Calculations indicated that the car would be more efficient with no conventional radiators but a heat exchanger set-up through an ice tank housed in the carbon nosebox of the vehicle. Every run with this system was a prototype. Adjustments were being constantly made to allow us to use the full thermal capacity available whilst holding the engine temperature to allow maximum power through each 11-mile pass.

The schedule to get the car designed, built, tested and flown to the States was optimistic to say the least. Inevitably, a six week build period spread to 6.5 weeks at which point we decided to move the almost complete car to RAF Wittering whilst we waited for the completion of the final few components. The car was put together at Visioneering in Coventry, a specialist engineering firm run by Brian Horner. F1 fans may well recognise that surname.

I’d put together a run plan for the car together with a sign off document which ran to some 140 separate systems and parts. It would work on a traffic light principle, and if there we no red lights after the Wittering trials, then we would pack the car off to Bonneville.

Working together almost around the clock for ten days allowed the all new team to gel and after over 20 runs we had that had achieved over 200mph in the space available on the runway and had only a couple of ‘amber’ warnings on the sign off document.

We had the green light for an assault on the salt!

Bonneville is like nowhere else on earth. In the winter it is a shallow salt lake which dries out in summer to form a dry lake bed with a flat and smooth (ish! depending on the weather) of some 46 square miles. Conditions vary from year to year and it sits at about 4200’ altitude, much the same as the top of Ben Nevis. The grip level on normal tyres is equivalent to wet tarmac and it took me quite some time to get used to a bright white surface which wasn’t as slippery as ice or snow. The light levels are something else, think sunshine on Alpine snow then double it. It’s somewhere you can suffer sunburn on the underside of your nose from the reflection. Ambient pressure is around 860 mb.

I was also in charge of the 'chutes. Developed by Andy and I as the testing progressed.

One of the biggest issues we faced prior to getting to Bonneville was finding tyres which would support our 2.7 tonne car at 350mph. We had settled on some 23” Goodyear drag race tyres which were validated to 300mph, then done our own tests to validate them to 350mph in very specific conditions on a rig at a USAF base used to develop the space shuttle tyres. With the correct run profile and pressures, they were capable of two 11 mile runs at that speed and load simulated on the steel roller rig.

The Bonneville program started at the annual ‘run what you brung’ Speed Week as practice, then a week of preparation including changing both engines to ‘record spec’ prior to an exclusive record week with the FIA in attendance. We were based a few miles from the salt flats at Wendover airport in a WW2 wooden framed hanger famous for housing the ‘Enola Gay’ aircraft the night prior to her little trip to Hiroshima in 1945…

In ‘that’ hanger

Speed week was a big learning experience and despite all that space, it wasn’t until the final day that the car ran over 300mph. There were, of course, all the normal little glitches of running a prototype, but the one that had us most perplexed was to become known as ‘lazy man on a tandem’ syndrome.

We were having trouble get one or other of the engines to spool up its turbos on the salt.

This had not been an issue on the dyno as the engine was always run against the resistance of the dyno brake to gain exhaust temperature, then the thermal inertia would spool up the turbos on request. It was never a problem at Wittering as the ambient pressure had been about 1000mb. But now with only 860mb pressure, one engine would start to spool up, take the load off the other and without load it would just give up and go along for the ride!

Just like the lazy tandem rider.

We tried pre-heating the engines to different levels, but as soon as one took off, the other would just become plain lazy! That slight ambient pressure drop had tipped our whole system over the edge.

There are very few people who have ever faced that problem (!) so we were really were pioneering.

Then it dawned on us......Andy and I confirm a few final details as the sun comes up over the salt

We plotted to attack the issue on two fronts. Firstly we would fit a 1” dia boost share line between the two engine plenums so that the engine that boosted first would share it around a bit.

We would also get Andy to load the engines against the brakes and have the exhaust gas temps displayed on the dash so he could see over 600 deg on each engine before allowing them to rev. So on the final day of speed week we set a record 317mph.

During our week of downtime we needed not only to rebuild to car but also to perfect our engine heating strategy by doing some low speed testing at Wendover airport.

The first run. with the new engines was halted when the rear engine refused to come on boost. After a few hours of digging into the data, it was spotted that the rear engine was seeing a false neutral signal from the gear box and was doing exactly what it was told and limiting its revs to 2800.

The following day, an electrical issue in the front loom meant we aborted the first run of the day, but by 10:30 that morning we had a new record of 328mph, with the return run at 342.

At the crack of dawn on 23 August our outbound run was 365mph. The tyres looked brand new, the cooling was almost perfect and Andy had not yet got into 6th gear.

The turnaround was completed in under 40 minutes and the car set off on its return run.

As we chased in our road cars it became clear that the big yellow car was not streaking away from us. Andy was on the radio saying the front engine was not boosting, but would give the brake loading one more shot. I thought that we had just wasted a good outbound run and my mind shifted to the plan for the following day.

But then, about a mile later into the run than it should have, the car came on to boost.

Talk about turbo lag! Andy then gave it the full beans and passed through the measured mile at 335mph, that’s what a mile less run up does.

The FIA announced the average as Andy came to rest at the end of the run 350.092mph.

It was very clear the car could go quicker. The tyres looked in fine shape and we had seen them to 400mph on a ‘free spin’ rig.

We had the team in place. If we hadn’t got ‘greedy’ with front engine start temperature we could do 2 x perfect runs. We still hadn’t turned the engines up to ‘11’. We hadn’t even run 6th gear yet! The salt was in the best condition for years and we had the place booked for another three days.

375mph looked entirely possible.

As the management team sat and discussed the possibilities we had all been infected by a very strong virus the locals call salt fever. Even Andy, normally the most controlled and rational person, was infected.

As our adrenaline levels subsided, so the prospect of running again looked more unlikely.

In the end we all agreed that to risk that we could come back with a better car and certified tyres another year, was much better idea than risking Andy the following day.

But it took us some hours to make that decision. But where was the man with the chequered flag?

The record has never been approached in the last 14 years.